Revision: 1, view history here.

Table of contents

eBPF, part 1

This article is the first in a series on eBPF. Each will build on the prior ones and progress from concepts and context towards examples and implementations. This first article will explore eBPF’s history, current state, and future trajectory. In doing so I hope to make the current state and function of eBPF more coherent. As with many software projects, eBPF can appear odd and spastic without the context of the history which shaped it.

This article also references future articles that will be written for this series. For those who may cite this article, it will be updated to reference said articles when they are posted. However, previous versions of this article will be accessible for reference and links to them will be posted on this page.

Intro

The Extended Berkeley Packet Filter, or eBPF for short, is difficult to explain and understand in its entirety. This is partially due to how different it is from prior efforts to solve the problems eBPF solves. Arguably, however, the biggest reason is its name. When someone first learns of eBPF they likely don’t know what BPF is or what it means for it to be “extended”. The world “Berkely” also isn’t helpful apart from referring to Berkeley, California, USA. The only words in eBPF’s name likely to have meaning to someone seeing them for the first time are “packet filter”. This gives no indication of the many things eBPF can be used for other than network filtering. Though, the Linux community didn’t realized how far eBPF would spread when it was named.

At its core eBPF is a highly efficient virtual machine that lives in the kernel. Its original purpose, efficient network frame filtering, made this virtual machine, and thus eBPF, an ideal engine for processing events in general. Because of this fact, there are currently twelve different types of eBPF programs, as of this writing, with many of them serving purposes unrelated to networking.

This article, “eBPF: Past, Present, and Future”, will walk through the history of BPF (eBPF’s predecessor), the current state of eBPF, and what the future may hold for it. In doing so this article aims to allow a reader, who has no familiarity with eBPF and intermediate familiarity with Linux, to have a firm grasp on the concepts and uses of eBPF along with providing a strong context for how it came to be what it is.

Clarifications, Terms, and Corrections

This article attempts to be as factually correct as possible while still being approachable to someone who knows nothing about the topic of eBPF. In setting such a lofty goal a few things are imminent.

- Clarifications. This article is intended to be readable for someone who has no familiarity with eBPF and intermediate familiarity with Linux. However, having spent many hours researching for this article, I expect there are details which appear obvious to me but not to those unfamiliar with the topic. This is not intentional but a result of spending over 40 hours with this content. If any part of this article needs more explanation or clarification please submit an issue to the Github repository for this website stating what needs more information.

- Terms. This article favors using technically correct terms over commonly used ones that are incorrect. One example of this is that the Berkeley Packet Filter, despite its name, filters network frames, not packets. The subsection below, titled Terms, lists all terms which may be misrepresented, for one reason or another, along with their explicit meaning in the scope of this article.

- Corrections. In writing this article I attempted to research, find, and cite as much evidence as possible for what is written here. That being said, this is an attempt to represent history, a field where these is always both more to say and multiple perspectives on everything. Thus, this article welcomes feedback and corrections with supporting evidence. Feedback can be submitted, with respective evidence, as issues to the Github repository for this website.

Terms

- BPF: The Berkeley Packet Filter, found in FreeBSD.

- eBPF: The Extended Berkeley Packet Filter, found in Linux.

- eBPF-map: General term for all different types of data stores available in eBPF. The documentation of eBPF refers to all eBPF data store types as “maps” even though there are multiple types, some of which are not maps. Thus this article uses the term eBPF-map to clearly designate the data store types of eBPF while not making it totally disconnected from eBPF’s own documentation.

- Network Frame: Unit of data for the link layer (layer 2) of the OSI network model. Example: Ethernet.

- Network Packet: Unit of data for the network layer (layer 3) of the OSI network model. Example: IPv4

- Network Segment: Unit of data for the transport layer (layer 4) of the OSI network model. Example: TCP

BPF and FreeBSD: The Past

To understand eBPF in Linux it is best to start with a different operating system: FreeBSD. In 1993 the paper “The BSD Packet Filter - A New Architecture for User-level Packet Capture, McCanne & Jacobson” was presented at the 1993 Winter USENIX conference in San Diego, California, USA. It was written by Steven McCanne and Van Jacobson who, at that time, were both working at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. In the paper, McCanne and Jacobson describe the BSD Packet Filter, or BPF for short, including its placement in the kernel and implementation as a virtual machine.

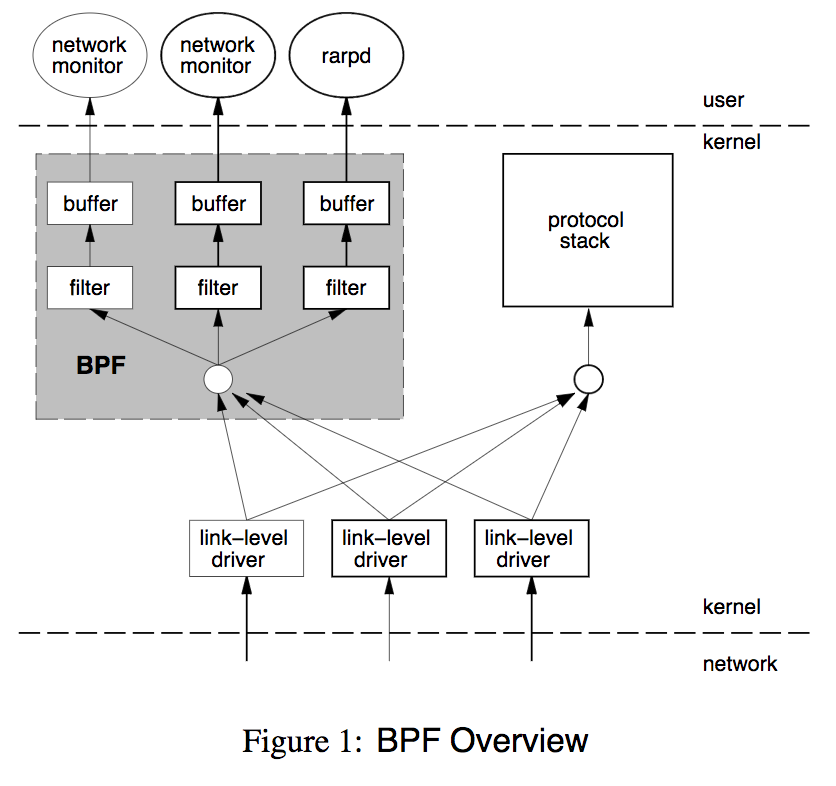

What BPF did so differently than its predecessors, such as the CMU/Stanford Packet Filter (CSPF), was to use a well thought out memory model and then expose it through an efficient virtual machine inside the kernel. By this, BPF filters can do traffic filtering in an efficient manner while still maintaining a boundary between the filter code and the kernel.

In their paper, McCanne and Jacobson’s offer the following diagram to help visualize this. Importantly, BPF employs a buffer between the filter and user-space to avoid having to make the expensive context switch between user-space and kernel-space for every packet the filter matches on.

Perhaps the most important thing that McCanne and Jacobson did was to define the design of the virtual machine by the following five statement:

- “It must be protocol independent. The kernel should not have to be modified to add new protocol support.”

- “It must be general. The instruction set should be rich enough to handle unforeseen uses.”

- “Packet data references should be minimized.”

- “Decoding an instruction should consist of a single C switch statement.”

- “The abstract machine registers[1] should reside in physical registers.”

This emphasis on expandability, generality, and performance is likely the reason why eBPF, in its modern form, encompasses vastly more than the original implementation of BPF did. Yet the BPF virtual machine was impressively simple and concise, it “consists of an accumulator, an index register, a scratch memory store, and an implicit program counter”.[McCanne and Jacobson] This can be seen by the example program, presented in register code, below which matches all IP packets. Explanations of each operation are to its right.

ldh [12] // load ethertype field info into register

jeq #ETHERTYPE_IP, L1, L2 // compare register to ethertype for IP

L1: ret #TRUE // if comparison is true, return true

L2: ret #0 // if comparison is false, return 0

Using only 4 virtual machine instructions, BPF is able to offer a highly useful IP packet filter!

To make a point about just how efficient this design was, the original BPF implementation was able to reject a packet with a minimum of only 184 CPU instructions.

This is the instruction count from the beginning to the end of the bpf_tap call meaning it measures both the work done by the BPF implementation plus the rejection filter.[2]

By this, BPF gave a processor comparable to those found in new graphing calculators the ability to process a theoretical max of 2.6 Gbps of network traffic through a safe kernel virtual machine.[3]

The efficiency of this can be emphasized by comparing it to context switching performance.

On a SPARCstation 2, the hardware used by McCanne and Jacobson to do these measurements, doing a context switch could take anywhere between 2,840 instructions and 16,000+ instructions (equivalent 71 microseconds and 400+ microseconds), depending on the number of processes competing for resources and size of contexts being swapped.[4]

Finally, it’s worth noting two things at the end of McCanne and Jacobson’s paper. First, that BPF was approximately two years old when their paper was published. This is noteworthy because it shows the development of BPF was a gradual one, something that continues with the technologies that succeeded it. Second, it mentions tcpdump as the most widely used program which utilizes BPF at the time of writing.[5] This means tcpdump, one of the most widely used network debugging tools today, has used BPF technology for at least 24 years! I mention this because no other writing seems mention how long the family of BPF technologies have been in use. When McCanne and Jacobson’s paper was published, BPF wasn’t a nifty idea with a alpha level implementation. It had been tested and used for two years and already found its way into multiple tools.

For those who are interested, McCanne and Jacobson’s paper is only 11 pages and a worthwhile read. A scan of the original paper can be found [here](/pdfs/The BSD Packet Filter - A New Architecture for User-level Packet Capture, McCanne & Jacobson, scan.pdf) and a PDF rendering of the draft can be found [here](/pdfs/The BSD Packet Filter - A New Architecture for User-level Packet Capture, McCanne & Jacobson, draft.pdf).[6][7]

eBPF and Linux: The Present

When Linux kernel version 3.18 was released in December 2014 it included the first implementation of extended BPF (eBPF).[8] What eBPF offers, in short, is an in kernel virtual machine, like BPF, but with a few crucial improvements. One, eBPF is more efficient than the original BPF virtual machine, thanks to JIT compiling of the eBPF code. Two, it is designed for general event processing within the kernel. This allows kernel developers to integrate eBPF into kernel components for whatever uses they see fit. And three, it includes efficient global data stores which eBPF calls “maps”. This allowed state to persist between events and thus be aggregated for uses including statistics and context aware behavior. It’s worth noting that since eBPF’s creation there are many types of data stores, not all of which are maps. However, the term “map” has stuck for referring to the different data store types and this article makes a compromise by referring to them as “eBPF-maps”.

With these abilities, kernel developers have rapidly utilized eBPF in a variety of kernel systems. In less than two and a half years these uses have grown to include network monitoring, network traffic manipulation, and system monitoring. Thus eBPF programs can be be used to switch network traffic, measure delays on disk reads, or track CPU cache misses.

Before continuing this article it’s worth making a quick clarification. The Linux community has a habit of referring to eBPF as simply “BPF”. Official documentation will usually reference eBPF as “eBPF” when speaking about it at a “high level”, away from the code. However, many implementation level naming conventions and pieces of documentation refer to it as “BPF”. To clear up any confusion before continuing, as of this article’s writing Linux only has eBPF and thus any references to BPF are really references to eBPF.[9] Some documentation related to Linux also uses “cBPF”, short for “classic BPF”, to refer to BPF and make the distinction between the two more clear.

The quickest way to understand the highlights of eBPF’s current implementation is to walk through what is required to use eBPF. The process eBPF programs go through can be broken down into three distinct parts.

-

Creation of the eBPF program as byte code. Currently the standard way of creating eBPF programs is to write them as C code and then have LLVM compile them into eBPF byte code which resides in an ELF file. However, the eBPF virtual machine’s design is well documented and the code for it and much of the tooling around it is open source. Thus, for the initiated, it is entirely possible to either craft the register code for an eBPF program by hand or write a custom compiler for eBPF. Because of eBPF’s extremely simple design all functions for an eBPF program, other than the entry point function, must be inlined for LLVM to compile it. This series will work through this in more detail with it’s third installment which hasn’t been posted yet. For those looking for more information in the mean time, please see the Further Reading section of this article.

-

Loading the program into the kernel and creating necessary eBPF-maps. This is done using the

bpfsyscall in Linux. This syscall allows for the byte code to be loaded along with a declaration of the the type of eBPF program that’s being loaded. As of this writing, eBPF has program types for usage as a socket filter, kprobe handler, traffic control scheduler, traffic control action, tracepoint handler, eXpress Data Path (XDP), performance monitor, cgroup restriction, and light weight tunnel. The syscall is also used for initializing eBPF-maps. This series second installment explains the options and implementation detail of this syscall with the article “eBPF part 2: Syscall and Map Types”. The third installment works through using current Linux tools, mainlytcandipfrom iproute2, for this purpose and ones following that will work through the low level operations of this in detail. For those looking for more information in the mean time, please see the Further Reading section of this article. -

Attaching the loaded program to a system. Because the different uses of eBPF are for different systems in the Linux kernel, each of the eBPF program types has a different procedure for attaching to its corresponding system. When the program is attached it becomes active and starts filtering, analyzing, or capturing information, depending on what it was created to do. From here user-space programs can administer running eBPF program including reading state from their eBPF-maps and, if the program is constructed in such a way, manipulating the eBPF map to alter the behavior of the program. For those looking for more information in the mean time, please see the Further Reading section of this article.

These three steps are simple in concept but highly nuanced in their utilization. Future articles will go into this in more detail and I will link to them in this article when they are done. In the mean time, know that the current tooling does provide a lot of assistance in using eBPF, even if it may feel contrary to the experience of using them. Like many things in Linux, it is perhaps nicer to use eBPF from inside the kernel than from outside of it with no assistance from other tooling. It is important to remember that the generality of eBPF is both what has lead to its amazing flexibility and the complexity of its use. For those who look to build new functionality around eBPF, the current Linux kernel provides more of a framework than an out of the box solution.[10]

To do a quick recap, eBPF has only been in the Linux kernel since 2014 but has already worked its way into a number of different uses in the kernel for efficient event processing. Thanks to eBPF-maps, programs written in eBPF can maintain state and thus aggregate information across events plus have dynamic behavior. Uses of eBPF continue to expanded due to its minimalistic implementation and lightening speed performance. Now onto what to expect for the future of eBPF.

Smart NICs and Kernel-Space Programs: The Future

In only a few years, eBPF has been integrated into a number of Linux kernel components. This makes the outlook of eBPF’s future both interesting but also unclear in direction. This is because there are really two futures in question: the future of uses for eBPF and the future of eBPF as a technology.

The immediate future of eBPF’s uses probably has the most certainty. It’s highly likely that the trend of using eBPF for safe, efficient, event handling inside the Linux kernel will continue. Because eBPF is defined by the simple virtual machine it runs on, there is also the potential for eBPF to be used in places other than the Linux kernel. The most interesting example of this, as of this writing, is with Smart NICs.

Smart NICs are network cards which allow processing of network traffic, to varying degrees, to be offloaded to the NICs themselves. This idea has been around since the early 2000’s, when some NICs started supporting offloading of checksum and segmentation, but only more recently has this been used for partial or full data plane offload. This new breed of Smart NICs goes by multiple names, including Intelligent Server Adapters, but generally feature programmable functionality and a large amount of memory for storing state. One example of this is Netronome’s Agilio CX line of SmartNICs which currently feature 10Gbps to 40Gbps ports paired with an ARM11 processor, 2GB of DDR3 RAM, and over a hundred specialized processing cores.[11]

Because of the large amount of processing power in them, recent Smart NICs have become a target for eBPF. With this, they pose a prime method for a variety of uses, including mitigating DoS attacks and providing dynamic network routing, switching, load balancing, etc. At the NetDev 1.2 conference in October 2016, Jakub Kicinski and Nic Viljoen of Netronome gave a presentation titled “eBPF/XDP hardware offload to SmartNICs”. In it Nic Viljoen states some very rough and early benchmarks of achieving 3 million packets per second for each FPC on a Netronome SmartNIC. As Viljoen goes on to point out, each SmartNIC has 72 to 120 of these FPCs, giving a hypothetical, though likely unrealistic, max eBPF throughput of 4.3 Tbps![12]

Finally there is the future of eBPF as a technology. Due to eBPF’s restrictive and simple implementation it offers a highly portable and performant way to process events. More than that, however, eBPF forces a change in how problems are solved. It removed objects and stateful code, instead opting for just functions and efficient data structures to store state. This paradigm vastly shrinks the possibilities of a program’s design, but in doing so it also makes it compatible with nearly any method of program design. Thus eBPF can be used synchronously, asynchronously, in parallel, distributed (depending on the coordination needs with the data store), and all other manner of program designs. Given this fact, I’d argue that a more fitting name for eBPF would be the Functional Virtual Machine, or FVM for short.

The biggest technological change that eBPF may usher in for future software is due to something that is easily forgotten about eBPF: it does JIT compilation of its bytes code into machine code for kernel-space execution! Because of this, the massive cost that the kernel forces on user-space programs due to hardware isolation, a drop in performance somewhere between 25% to 33%, is avoided by eBPF.[13] This means that a user program could run up to 50% faster by being run on an kernel-space virtual machine![14] This idea, in fact, isn’t a new one. In 2014, Gary Bernhardt gave an amusing and fascinating talk at PyCon titled “The Birth and Death of Javascript”. In it Bernhardt references this same statistic on hardware isolation cost as he explains how, in a fictitious future, the majority of all software runs on an in-kernel Javascipt virtual machine. In such a future, software portability is far less of a problem because software isn’t compiled to a hardware architecture but to Javascript. He even goes on to say that an implementation of a Document Object Model (DOM), the data store in a browser that holds the state of a web-page for rendering, has also been moved into the kernel where it now runs the windowing system. This is quite similar in concept to eBPF-maps, which could be theoretically used for something like this in the future. While it is light hearted in some ways, there’s no denying that Bernhardt’s presentation is built upon sound facts and may be right about a future where computer program isolation is done by a kernel-space virtual machine, not hardware. We’ll simply have to wait to see if eBPF becomes the champion of that change.

Further Reading

There are plenty of resources out there related to eBPF, however I have yet to find one that is approachable, coherent, and complete. This is in part due to the rapid progress being done on it and in part due to the relatively scarce documentation efforts on it. While I’ve started this series on eBPF to help add documentation and writings related to eBPF, I fully acknowledge that other resources cover different aspects of eBPF better. For those looking for more material and documentation related to eBPF, here are the best ones I have found.

-

Quentin Monnet of 6WIND has put together the undisputed best compilation of resources related to eBPF that I have seen. This compilation, which he continues to update, can be found as a post on his blog.

-

The BCC project maintains a convenient list of eBPF features including the kernel version they were released with and the commit that added them to the kernel.

-

The Cilium project maintains a thorough reference guide on eBPF and XDP on their documentation site. A brief writeup on the intentions of the reference guide can be found in a blog post on Cilium’s website.

For those looking to continue reading this series, please check out the next installment, “eBPF part 2: Syscall and Map Types”

-

“Abstract machine” in the phrase the paper uses to refer to BPF’s virtual machine. ↩︎

-

This number comes from the fact that a rejection took ~4.6 microseconds and the computer they were running it on, a SPARCstation 2, had a 40MHz processor. Result of: (4.6 usec)(40 MHz), Wolfram Alpha calculation. ↩︎

-

Result of: (1500 bytes / Hz)/(4.6 usec), Wolfram Alpha calculation. ↩︎

-

Source http://manpages.ubuntu.com/manpages/trusty/lat_ctx.8.html ↩︎

-

As a fun fact, Steven McCanne was also one of the original authors of tcpdump, along with Van Jacobson and Craig Leres, all of whom were working at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. ↩︎

-

Cached from link on 2017-04-20, https://www.usenix.org/legacy/publications/library/proceedings/sd93/mccanne.pdf ↩︎

-

Cached from link on 2017-04-20, http://www.tcpdump.org/papers/bpf-usenix93.pdf ↩︎

-

It is true that eBPF first appeared in Linux kernel 3.18, but there is some minor historical context missing from that statement. What was released in Linux kernel 3.18 was the

bpfsyscall. However, the work building up to that, including the JIT compiler, first started appearing with kernel version 3.15. ↩︎ -

There is one exception to this statement. On August 18th, 2003 the SCO Group (SCO) gave a presentation in Las Vegas which “alleged infringement by the Linux developers” [Perens]. SCO referred to specific pieces of code in Linux including an implementation of BPF [Perens]. As best I could find from documents on the matter, the code related to this alleged infringement was written by Jay Schulist who appears to have implemented a BPF virtual machine in the Linux kernel [Perens]. From my findings it appears Schulist’s implementation did not take code from prior software but instead implemented it by following documentation on the virtual machine’s specifications [Perens]. The accusation does not appear to have resulted in any action since SCO did not own the original BPF code [Perens]. Regardless, I was unable to find any references to the original BPF virtual machine existing in Linux outside those referring to this event. This could be due to the Linux kernel’s frequent use of “BPF” to refer to eBPF which undoubtedly making finding any references to BPF, prior to eBPF’s inception, much harder. At the very least, it appears that if BPF did exist in the Linux prior to eBPF it was not highly used or changed and thus would have simply been succeeded by eBPF. Source on SCO controversy with Linux comes from Bruce Perens: http://web.archive.org/web/20030828144050/perens.com/Articles/SCO/SCOSlideShow.html ↩︎

-

Then again, if you’re a Linux kernel developer looking to utilize eBPF, you probably already knew that. ↩︎

-

Specs of the CX line can be found here: https://www.netronome.com/products/agilio-cx/ ↩︎

-

Worlfram Alpha math, (3e6 * 1500 bytes / second) * 120: https://www.wolframalpha.com/input/?i=(3e6++1500+bytes+%2F+second)++120 ↩︎

-

Research done by Mark Aiken, Manuel Fähndrich, Chris Hawblitzel, Galen Hunt, and James Larus for Microsoft found that “hardware-based isolation incurs non-trivial performance costs (up to 25-33%) and complicates system implementation”, source: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/publication/deconstructing-process-isolation/ ↩︎

-

This is number may seem unintuitive considering that it was just stated that hardware isolation incurs a 33% performance penalty, not a 50%. The reason is because this is the inverse. If something runs at 67% of it’s maximum speed then it’s maximum speed is 1 divided by 0.67 of it’s current speed, or 50% more. ↩︎

Return to top

For those wishing to share feedback or comments with me on this article please refer to the Contact section on the About page.